|

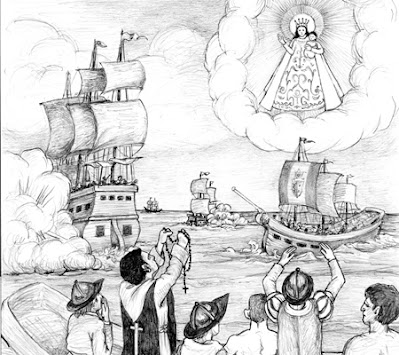

| Illustration showing the Battle of Naval de Manila to appear in The Story of the Philippines. |

The more one delves into history, the more one is humbled by what one doesn’t know. Case in point...

In the first shock, one hundred and fifty of the finest buildings, which in other cities would be called palaces, were totally destroyed; all the other houses were so damaged and dangerous that it has been necessary to demolish them completely. It may be said with truth that only a semblance of Manila remains....Whole Indian villages were overthrown, as their huts are built of so light materials, bamboos and palm-leaves; and hills were leveled. Rivers were dried, which afterward flowed again; others leaving their beds, inundated the villages; great fissures and even chasms, appeared in the open fields. In the Manila River, the disturbance and commotion in its waves was so great that it seemed as if they would flood all the country. [Fayol, Relation of the events on sea and land in the Filipinas Islands...]

In [the Encarnación] were mounted thirty-four pieces of artillery, all of bronze and of the reinforced class, which variously carried balls of thirty, twenty-five, and eighteen pounds. The [Rosario] was equipped with as many as thirty pieces, of the same capacity—although on account of the deficiency in this sort of artillery, it was necessary to dismantle some posts in the fortifications of this city and of Cavite.

The governor-general of the Philippines, Don Diego Fajardo, chose General Lorenzo de Orella as commander and chief of the Spanish squadron. Fr. Fayol offers this heroic description of Don Orella:

...General Lorenzo de Orella y Ugalde, a Biscayan, under whose charge the vessels had sailed from Acapulco [was chosen] not only because of his proved bravery, his experience in the art of war, and his services and commands in both the Northern and Southern Seas, as well as in these islands (particularly in Mindanao, where he fought hand-to-hand with a gigantic Moro and killed him), but because of his well-known Christian spirit of modesty—which, for success, are no less important than valor.

Not trusting to mere earthly power, however, Don Fajardo agreed to allow four priests to accompany the flotilla, two in each ship. As both ships bore religious names, they were sent forth under the protection of Our Lady, the Virgin Mary. Fr. Fayol explains:

As a result of excellent teaching and the fervor of these fathers, arrangements were made that all of the men should, in the first place, purify their consciences with the holy sacraments of penance and communion; that they should take as their special patron saint the Virgin of the Rosary; that in order to bind her further, they should vow to her a feast-day in thanksgiving for the victories which they expected to receive through her agency; and that every day all should recite their prayers aloud, on their knees, and in two choirs—the prayers of the rosary before our Lady's image, the litanies of the most holy name of Mary, and finally an act of contrition.

Beyond these acts of piety, Don Fajardo caused the Blessed Sacrament to be exposed in several churches throughout Manila from the time of the departure of the galleons until their expected return.

When all was made as ready as temporal and spiritual efforts would allow, the Spanish ships boldly sallied forth to meet the more numerous Dutch in what should have been a very lop-sided affair. However, as Fr. Fayol admits, the Spanish had one thing going in their favor. The hoped-for coordination of the Dutch fleets failed and each one arrived on station at different times, allowing the Spanish the opportunity to fight each of them in detail. The first fleet arrived in Spanish waters in early March and were detected by the Spanish on March 15. Fr. Fayol provides an excellent account of the battle which followed, and I am only too happy to allow his voice to describe the proceedings:

On arriving at the entrances of Mariveles, the [Spanish] ships were placed in battle array, the artillery loaded, the matches lighted and the linstocks ready, the rigging free, and other preparations made. This was done because the sentinels [on Mariveles Island] warned our men that the enemy were, with their squadron, not far from that place; and that they might expect at any moment to encounter the Dutch—although in fact the latter were not descried until the fifteenth of the said month of March. At nine o'clock in the morning of that day, our almiranta [the Rosario] which had pushed ahead of the flagship perhaps half a league, and was sailing with a northwest wind—fired two cannon-shots and lowered the maintop-sail as a signal that it descried the enemy. The flagship put about, and followed her, and from the maintop they soon saw a sail in the distance, but it was impossible to overtake it; and it soon disappeared, because it was favored by a fresher wind than our ships had.

After that, our galleons were left becalmed until one o'clock; and at that hour were descried from the flagship four hostile sails, which were sailing toward her aft, with an east wind. It was two hours before they reached the flagship, and in that space of time the men were stationed, the ships cleared, the posts reconnoitered, and all other arrangements made, both spiritual and temporal, required by the occasion. The almiranta fell two ship-lengths astern of the flagship, and in this position the ships awaited the enemy, in order to fight them.

As soon as the enemy came near, they extended all their ships, and without attempting to give a broadside to our flagship, passed, in line to larboard, and the enemy's flagship began the battle by firing a cannon. Our commander immediately commanded that response be made with two shots—one with a thirty-pound ball and a cylinder of the same weight, which tore open all their cutwater at the bow. The enemy's ship went on in this condition, and the others continued to exchange shots with our flagship. Recognizing their own strength, the enemy tried to approach the almiranta, which they supposed was not so well armed, being a smaller ship. But they were received with equal valor and spirit on our side, our vessels firing so often and throwing so many balls that they could not be counted.

The fight lasted about five hours, and the mortality and damage were so great that all the anxiety that the heretics had felt to reach our ships when they thought to conquer us was now directed to separating themselves from us. They anxiously awaited the night, which was now approaching, to make their cowardly escape, which they did with lights extinguished. But the enemy's almiranta did not succeed in doing this in safety. It had been the most persistent in the attack upon our flagship, and remained to our leeward. It was so badly damaged that its cannon could not be fired, and hardly could it flee. Our ship was so near it that our commander had the men ready at the bow to board the Dutch ship, but the darkness of night forced us to abandon the chase, on account of the danger from the shoals which the pilots declared were in that place. It was noticed that the enemy did not use lanterns as they had formerly done, seeking protection for their armada. Our commander ordered that they be used in our ships, and that the lights be allowed to shine very brightly, in order that the enemy might come to look for us.

Our people fully intended to renew the pursuit at daybreak, to finish their defeat, but when day came our two galleons found themselves alone, and did not know what course the enemy had taken. They followed the Dutch, in the direction which they thought most probable, as far as Cape Bojeador, which is at the farthest end of this island of Manila. From there our ships returned, as the coasts were now secure, to the port of Bolinao, in order to send to this city dispatches announcing the result of the battle.

This was regarded as a brilliant victory, not only because of the disparity in the number of ships, but because of the little damage our side had sustained. In that battle not a man was killed, and comparatively few were wounded. It was evident that the enemy's loss was great, although we could not then ascertain it correctly. But afterwards we learned that many had been killed and wounded, and that two of their vessels were rendered useless.

All these exploits are worthy of great praise...According to the estimate made by well-informed persons, although we fired, in these battles, over 2,000 cannon-shots, and the enemy over five thousand, we had only fourteen killed, and comparatively few wounded. While the enemy, besides the vessels which we sank, arrived at their forts so damaged, and had lost so many men, that for many a year they will remember the two stout galleons of Manila....Thanksgiving was celebrated by a solemn fiesta, a procession, divine worship, and [a parade of] the squadron, with other demonstrations in fulfillment of the vow made to the Virgin of the Rosary, the city making a new vow to continue this anniversary every year.

[All of the above quotes are taken from Fray Joseph Fayol's Relation of the events on sea and land in the Filipinas Islands during the recent years, until the earthquake and destruction on the feast of St. Andrews in 1645; and the battles and naval victories over the Dutch in 1646. The English translation of this work is taken from The Philippine Islands, 1493-1898, Volumes 34-35, edited by Emma Helen Blair, James Alexander Robertson, 1906.]

|

| The image of Our Lady of La Naval de Manila. |

No comments:

Post a Comment