|

| The Martyrdom of Saint Agnes as portrayed in a very Renaissance style by Paolo Guidotti, late 16th century. |

Though no authentic account of her trial has survived antiquity, the passion of Saint Agnes is known from three near contemporary ancient sources. The first is an epitaph which was affixed to her tomb in the catacombs by Pope Damasus in the late 4th century AD. The marble slab containing this epitaph may be seen to this day at the basilica of Saint Agnes in Rome. It reads as follows (in English translation):

Report says that when she had recently been snatched away from her parents, when the trumpet pealed forth its terrible clangor, the virgin Agnes suddenly left the breast of her nurse and willingly braved the threats and rage of the tyrant who wished to have her noble form burned in flames. Though of so little strength she checked her extreme fear, and covered her naked members with her abundant hair lest mortal eye might see the temple of the Lord. O thou dear one, worthy to be venerated by me! O sacred dignity of modesty! Be thou favorable, I beseech thee, O illustrious martyr, to the prayers of Damasus!

|

| The original epitaph of Pope Damasus commemorating the grave site of Saint Agnes, ca. 370s AD. |

It is the birthday of Saint Agnes, let men admire, let children take courage, let the married be astounded, let the unmarried take an example. But what can I say worthy of her whose very name was not devoid of bright praise? In devotion beyond her age, in virtue above nature, she seems to me to have borne not so much a human name as a token of martyrdom, whereby she showed what she was to be...

...She is said to have suffered martyrdom when twelve years old. The more hateful was the cruelty which spared not so tender an age, the greater in truth was the power of faith which found evidence even in that age. Was there room for a wound in that small body? And she who had no room for the blow of the steel had that wherewith to conquer the steel. But maidens of that age are unable to bear even the angry looks of parents and are wont to cry at the pricks of a needle as though they were wounds. She was fearless under the cruel hands of the executioners, she was unmoved by the heavy weight of the creaking chains, offering her whole body to the sword of the raging soldier as yet ignorant of death but ready for it. Or if she were unwillingly hurried to the altars, she was ready to stretch forth her hands to Christ at the sacrificial fires, and at the sacrilegious altars themselves to make the sign of the Lord the Conqueror, or again to place her neck and both her hands in the iron bands, but no band could enclose such slender limbs.

A new kind of martyrdom! Not yet of fit age for punishment but already ripe for victory, difficult to contend with but easy to be crowned, she filled the office of teaching valor while having the disadvantage of youth. She would not as a bride so hasten to the couch, as being a virgin she joyfully went to the place of punishment with hurrying step, her head not adorned with plaited hair but with Christ. All wept, she alone was without a tear. All wondered that she was so readily prodigal of her life, which she had not yet enjoyed, and now gave up as though she had gone through it. Everyone was astounded that there was now one to bear witness to the Godhead, who as yet could not, because of her age, dispose of herself. And she brought it to pass that she should be believed concerning God, whose evidence concerning man would not be accepted. For that which is beyond nature is from the Author of nature.

What threats the executioner used to make her fear him, what allurements to persuade her, how many desired that she would come to them in marriage! But she answered: “It would be an injury to my Spouse to look on any one as likely to please me. He who chose me first for Himself shall receive me. Why are you delaying, executioner? Let this body perish which can be loved by eyes which I would not.”

She stood, she prayed, she bent down her neck. You could see the executioner tremble as though he himself had been condemned, and his right hand shake, his face grow pale as he feared the peril of another, while the maiden feared not for her own. You have then in one victim a twofold martyrdom, of modesty and of religion. She both remained a virgin and she obtained martyrdom.

|

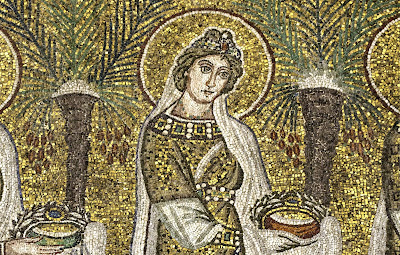

| Saint Agnes among the procession of female martyrs portrayed in mosaic in the nave of Saint Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna, 6th century AD. |

Within the walls of Rome is laid

Agnes, brave martyr, holy maid;

Twice blest, a martyr’s death to die

And to preserve her chastity.

’Tis said, as yet of tender age,

But strong in love, that she defied

The edict and the prætor’s rage,

Still faithful to the Crucified.

By threats and blandishments assailed

In vain, she wavered not nor quailed;

Dauntless and resolute, whate’er

Man’s malice can devise to bear.

Then spake the judge: “This stubborn maid

May hold life cheap, nor be afraid

To bear the lash, and yet may be

Chary of her virginity.

Unless the maiden will incline

Her head before Minerva’s shrine,

Fling her among the vile to be

A toy for foulest ribaldry!”

She said, “I am not left alone:

Christ will not so forget his own.

Bloodstained the sword will be—but I,

Christ helping me, unstained shall die.”

|

| Click here for info. |

Although Prudentius’s account contains details which modern readers may find incredible, all three of these ancient sources corroborate the principal facts of Saint Agnes’s martyrdom and bear witness to her extraordinary passion and death.

All three of the above excerpts, along with numerous other accounts of the ancient martyrs, may be found in I Am A Christian: Authentic Accounts of Christian Martyrdom and Persecution from the Ancient Sources.