In G. K. Chesterton's

The Everlasting Man, we have an author of true genius and incredible literary ability covering an enormous range of subjects with the philosophical acumen of a Renaissance polymath. I, on the other hand, am an average fellow with decent reading skills and a rudimentary understanding of theology and philosophy. Therefore, it is fairly ludicrous for me to attempt a critique of this book.

But don't think that will stop me.

I read 100% of

The Everlasting Man. But I readily admit that if I understood 50% of it, I did well. Like much of Chesterton's work, the book is more like 40,000 aphorisms strung together than a systematic treatise on a single subject. In it, Chesterton attempts to parallel the celebrated

Outline of History by H. G. Wells which had been published in 1919, some 5 years before. But while Wells's work was a materialist history that was criticized by Hillaire Belloc as giving less space to Christ than to the Persian campaign against the Greeks, Chesterton's work focuses on how the reality of Christ and the truth of Christianity has infused all of human history.

As someone who already believes this thesis, Chesterton's work was mostly preaching to the choir in my case. So perhaps the book did not have the same impact on me as it might have on someone who subscribes to the materialist version of history going in. It certainly impacted C. S. Lewis,

who gave the work a good bit of credit for his conversion to belief in Christianity.

Chesterton makes the point repeatedly that Christianity is unique and should not be compared to other religions. Unlike Jesus, the founders of other religious traditions never claimed to actually

be God. Chesterton writes: "Mahomedans did not misunderstand Mahomet and suppose he was Allah. Jews did not misinterpret Moses and identify him with Jehovah." Instead, the claim made by Christ stands alone among philosophers and great lawgivers. Any others who actually did make such a claim, were deemed madmen: "No one can imagine Aristotle claiming to be the father of gods and men, come down from the sky; though we might imagine some insane Roman Emperor like Caligula claiming it for him, or more probably, for himself."

And that leaves us with a dilemma that utterly demolishes the comforting popular notion that Jesus was merely a wise rabbi who passed on a moral code to his disciples. As C. S. Lewis would later put it more succinctly:

"Either this man was, and is, the Son of God: or else a madman or something worse."There is so much more to this book than I can do justice to here. Rather than go on at length, I will simply give the reader a few choice quotes which will exhibit Chesterton's point of view and rhetorical style far better than my continued rambling:

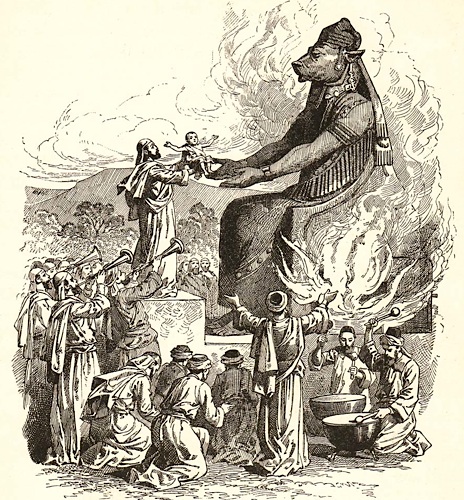

"Far away to the east there is a high civilization of vast antiquity in China; there are the remains of civilizations in Mexico and South America and other places, some of them apparently so high in civilization as to have reached the most refined forms of devil-worship."

"Now it is very right to rebuke our own race or religion for falling short of our own standards and ideals. But it is absurd to pretend that they fell lower than the other races and religions that professed the very opposite standards and ideals. There is a very real sense in which the Christian is worse than the heathen, the Spaniard worse than the Red Indian, or even the Roman potentially worse than the Carthaginian. But there is only one sense in which he is worse; and that is not in being positively worse. The Christian is only worse because it is his business to be better."

"The truth is that only men to whom the family is sacred will ever have a standard or a status by which to criticize the state. They alone can appeal to something more holy than the gods of the city; the gods of the hearth."

As should be readily appreciated from these quotes, there is much in this book that is directly applicable to our own times. But these are only the barest sample of Chesterton's wit and wisdom. Practically every fourth line of this book is quotable.

In short, I heartily recommend

The Everlasting Man. However, let the reader beware: Chesterton assumed a level of knowledge and intellectual patience that is quite honestly beyond most of us today. As a result, I found the book to be somewhat frustrating because so much of it is so clearly over my head.

On this day in AD 493, Odovacar, the Scirian king of Italy concluded a treaty with Theodoric the Ostrogoth which effectively ended the war between them.

On this day in AD 493, Odovacar, the Scirian king of Italy concluded a treaty with Theodoric the Ostrogoth which effectively ended the war between them.