|

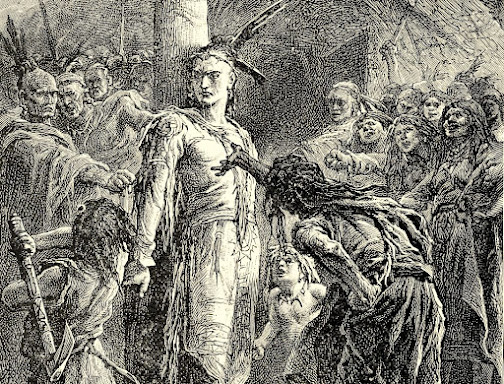

| The death of St. Charles Garnier, as depicted in a French woodcut. |

For the feast of the North American martyrs today, I post the account of Saint Charles Garnier's death and life as taken from the Jesuit Relation of 1650. Garnier was slain by the Iroquois on December 7, 1649 at the age of 44.

Fr. Garnier's death occurred during that year of destruction, 1649, when the Iroquois erupted like a whirlwind from their base in present-day central New York and burst upon their traditional enemies to the north. Newly equipped with British muskets and schooled in their use, the Iroquois had an insuperable advantage over the Hurons, Algonquins, and Tobacco nations who were still armed with their more primitive traditional weapons.

Fr. Garnier was a missionary among the Petun (or Tobacco) nation, allies of the Hurons who lived south of Georgian Bay in present-day Ontario. During that winter of 1649, news had gone out to the Petun that an Iroquois war party was headed their way. Rather than await the arrival of these raiders, the Petun warriors set out to find and destroy them in the wilderness. Unfortunately, their ambush was misled and the stealthy Iroquois arrived unopposed at the defenseless Petun villages.

The account below was drawn from the testimony of eye-witnesses who escaped the attack, and those who found his remains after the Iroquois withdrew:

It was on the seventh day of the month of last December, in the year 1649, toward three o'clock in the afternoon, that this band of Iroquois appeared at the gates of the village, spreading immediate dismay, and striking terror into all those poor people—bereft of their strength, and finding themselves vanquished when they thought to be themselves the conquerors. Some took to flight. Others were slain on the spot. To many, the flames, which were already consuming some of their cabins, gave the first intelligence of the disaster. Many were taken prisoners; but the victorious enemy, fearing the return of the warriors who had gone to meet them, hastened their retreat so precipitately, that they put to death all the old men and children, and all whom they deemed unable to keep up with them in their flight.

It was a scene of incredible cruelty. The enemy snatched from a mother her infants, that they might be thrown into the fire; other children beheld their Mothers beaten to death at their feet or groaning in the flames—permission, in either case, being denied them to show the least compassion. It was a crime to shed a tear, these barbarians demanding that their prisoners should go into captivity as if they were marching to their triumph. A poor Christian Mother, who wept for the death of her infant, was killed on the spot, because she still loved, and could not stifle soon enough her natural feelings.

Father Charles Garnier was, at that time, the only one of our Fathers in that Mission. When the enemy appeared, he was just then occupied with instructing the people in the cabins which he was visiting. At the noise of the alarm, he went out, going straight to the Church, where he found some Christians. "We are dead men, my brothers," he said to them. "Pray to God, and flee by whatever way you may be able to escape. Bear about with you your faith through what of life remains; and may death find you with God in mind."

He gave them his blessing, then left hurriedly, to go to the help of souls. A prey to despair, not one dreamed of defense. Several found a favorable exit for their flight. They implored the Father to flee with them, but the bonds of Charity restrained him. All unmindful of himself, he thought only of the salvation of his neighbor. Borne on by his zeal, he hastened everywhere—either to give absolution to the Christians whom he met, or to seek, in the burning cabins, the children, the sick, or the catechumens, over whom, in the midst of the flames, he poured the waters of Holy Baptism, his own heart burning with no other fire than the love of God.

It was while thus engaged in Holy work that he was encountered by the death which he had looked in the face without fearing it, or receding from it a single step. A bullet from a musket struck him, penetrating a little below the breast; another, from the same volley, tore open his stomach, lodging in the thigh, and bringing him to the ground. His courage, however, was unabated. The barbarian who had fired the shot stripped him of his cassock, and left him, weltering in his blood, to pursue the other fugitives.

This good Father, a very short time after, was seen to clasp his hands, offering some prayer; then, looking about him, he perceived, at a distance of ten or twelve paces, a poor dying Man—who, like himself, had received the stroke of death, but had still some remains of life. Love of God, and zeal for Souls, were even stronger than death. Murmuring a few words of prayer, he struggled to his knees, and rising with difficulty, dragged himself as best he might toward the sufferer, in order to assist him it dying well. He had made but three or four steps when he fell again, somewhat heavily. Raising himself for the second time, he got, once more, upon his knees and strove to continue on his way; but he body, drained of its blood, which was flowing in abundance from his wounds, had not the strength of his courage. For the third time he fell, having proceeded but five or six steps.

Further than this, we have not been able to ascertain what he accomplished—the good Christian woman who faithfully related all this to us having seen no more of him, being herself overtaken by an Iroquois, who struck her on the head with a war-hatchet, felling her upon the spot, though she afterward escaped. The Father shortly after, received from a hatchet two blows upon the temples, one on either side, which penetrated to the brain. To him it was the recompense for all past services, the richest he had hoped for from God's goodness. His body was stripped, and left, entirely naked, where it lay.

Two of our Fathers, who were in the nearest neighboring Mission, received a remnant of these poor fugitive Christians, who arrived all out of breath, many of them all covered with their own blood. The night was one of continual alarm, owing to the fear, which had seized all, of a similar misfortune. Toward the break of day, it was ascertained from certain spies that the enemy had retired. The two Fathers at once set out, that they might themselves look upon a spectacle most sad indeed, butt nevertheless acceptable to God. They found only dead bodies heaped together, and the remains of poor Christians—some who were almost consumed in the pitiable remains of the still burning village; others deluged with their own blood; and a few who yet showed some signs of life, but were all covered with wounds,—looking only for death, and blessing God in their wretchedness. At length, in the midst of that desolated village, they descried the body they had come to seek; but so little cognizable was it, being completely covered with its blood, and the ashes of the fire, that they passed it by. Some Christian Savages, however, recognized their Father, who had died for love of them. They buried him in the same spot on which their Church had stood, although there remained no longer any vestige of it, the fire having consumed all.

The poverty of that burial was; sublimed sanctity no less so. The two good Fathers divested themselves of part of their apparel, to cover therewith the dead; they could do no more, unless it were to return entirely unclothed...

Two days after the taking and burning of the village, its inhabitants returned—who, having discovered the change of plan which had led the enemy to take another route, had had their suspicions of the misfortune that had happened. But now they beheld it with their own eyes; and at the sight of the ashes, and the dead bodies of their relatives, their wives, and their children, they maintained for half the day a profound silence—seated, after the manner of savages, upon the ground, without lifting their eyes, or uttering even a sigh—like marble statues, without speech, without sight, and without motion. For it is thus that the Savages mourn—at least, the men and the warriors—tears, cries, and lamentations befitting, so they say, the women.

At this point, the author of the relation, Fr. Paul Ragueneau, provides a brief biography of his Jesuit colleague, Fr. Garnier.

Father Charles Garnier was born in Paris, in the year 1605, and entered our Society in 1624. He was thus but little over 44 years of age on the 7th of December, 1649—the day on which he died in labors which were truly Apostolic, and in which he had lived since the year 1636, when he left France and went up to the country of the Hurons.

From his infancy, he entertained the most tender sentiments of piety, and, in particular, a filial love toward the most holy Virgin, whom he called his Mother. "It it she," he would say, "who carried me in her arms through all my youth, and has placed me in the Society of her Son." He had made a vow to uphold, until death, her Immaculate Conception. He died on the eve of that august Festival [December 8], that he might go to solemnize it yet more gloriously in Heaven.

From the time of his Novitiate, he seemed an angel, his humility being so uncommon that he was held before all others as a mirror of sanctity. He had experienced the greatest difficulties in obtaining permission from his father to enter our Society; but these were very much enhanced when, ten years after that first separation, it became necessary to reconcile the father to a second, of a still more painful kind. This was his departure from France, to go into these Missions at the end of the world—our Superiors having expressed their wish that his father should yield consent to this, on account of peculiar obligations which our Society was under to him. His voyage was thus delayed, an entire year, but this only served to fan the flame of his desires. Day and night he thought only of the conversion of the savages, and of devoting to them his life, to its latest breath....At length, he succeeded in obtaining this great boon from Heaven, and with so much joy in his heart, that he looked upon that day as the happiest of his entire life.

While crossing the sea, he made some remarkable conversions on shipboard. Among others, he was informed that belonging to the crew was a man without conscience, without Religion, and without God. This man avoided every one, and all avoided him. It was over ten years since he had confessed. The Father, carried away by his usual zeal, took in hand that gloomy temper and that hopeless man, and, after a thousand evidences of love—exhibited in all manner of attentions, instructions, and good of fines—succeeded at last in winning him. He induced this man to make a general confession, and brought him into so great a peace, and joy of conscience, that all wondered, and were touched by it.

As soon as he came among the Hurons, we had in him an indefatigable worker, replete with every gift of Nature and of Grace that could make an accomplished Missionary. He had mastered the language of the Savages so thoroughly that they themselves were astonished at him. He worked his way so far into their hearts, and with such a power of eloquence, as to carry them away with him. His face, his eyes—even his laugh, and every movement of his body—preached sanctity. His heart spoke yet louder than his words and made itself heard, even in his silence. I know of several who were converted to God by the mere aspect of his countenance, which was truly Angelic, and which imparted a spirit of devotion, and chaste impressions, to those approaching him—whether he were at prayer, of seemed to be communing with himself, collecting his thoughts, after some activity in behalf of his neighbor; or whether he spoke of God; or it might be, even, when Charity had engaged him in discourse of a different character, which afforded some relaxation to his mind. The love of God which reigned in his heart gave life to all his movements, and made them heavenly.

His virtues were heroic, nor was there lacking in him one of those which go to make up the greatest Saints....His prayers were so full of reverence for the presence of God, and so peaceful in the hush of all his own powers, that he scarcely seemed to suffer the least distraction, though engaged in occupational most apt to dissipate his thoughts. His Prayers, from the outset, were but a series of colloquies, devout emotions, and acts of love; and this ardor grew even more intense until the close.

His mortification was equal to his love. He sought it night and day. He always lay on the bare ground, and bore constantly upon his body some portion of that Cross which during life he held most dear, and on which it was his desire to die. Every time that he returned from his Mission rounds he never failed to sharpen freshly the iron points of a girdle all covered with spur-rowels, which he wore next to his skin. In addition to this, he would very often use a discipline of wire, armed, besides, with sharpened points. His daily fare differed in no way from that of the savages—that is to say, it was the scantiest that a miserable beggar would expect in France. During that last year of famine, acorns and bitter roots were, to him, delicacies—not that he was insensible to their bitterness, but that love gave a relish to them. And yet he had ever been the cherished child of a rich and noble house, and the object of all a Father's endearments....

In his latest letters, addressed to me three days before his death, in response to a request which I made to him touching the state of his health—asking if it would not be right that he should quit for a time his Mission, in order to come once more to see us, and recover a little his strength—he answered me by urging, at great length, many reasons which disposed him to remain in his Mission, but reasons which gathered their force only from the spirit of charity and truly Apostolic zeal with which he was filled. "It is true," he added, "that I suffer something in regard to hunger, but that is not to death; and, thank God, my body and my spirit keep up in all their vigor. I am not alarmed on that side. But what I should fear more would be that, in leaving my flock in the time of their calamities, and in the terrors of war—in a time when they need me more than ever—I would fail to use the opportunities which God gives me of losing myself for him, and so render myself unworthy of his favors. I take only too much care of myself," added he; "and if I saw that my powers were failing me, I should not fail, since your Reverence bids me, to come to you; for I am at all times ready to leave everything, to die, in the spirit of obedience, where God wills. But otherwise, I will never come down from the Cross on which his goodness has placed me."

These great aspirations after sanctity had grow with him from his infancy. For myself, having known him for more than twelve years—in which he opened to me all his heart, as he did to God himself—I can truly say that, in all those years, I do not think that, save in sleep, he has spent a single hour without these burning and vehement desires of progressing more and more in the ways of God, and of helping forward in them his fellow-creatures. Outside of these considerations, nothing in the world affected him—neither relatives, nor friends, nor rest, nor consolation, nor hardships, nor fatigues. God was his all; and, apart from Him, all else was to him as nothing.

He took some sick people, and carried them on his shoulders for one or two leagues, in order to gain their hearts and to secure the opportunity to baptize them. He accomplished some ten or twenty leagues during the most excessive heat of Summer, along dangerous roads, where the enemy was continually perpetrating massacres. All breathless, he would hurry after a single savage, who served him as guide, that he might baptize some dying man, or a captive of war who was to be burnt that same day. He has passed whole nights in groping after a lost path, amid the deep snows and the most biting cold of winter—his zeal knowing no obstacle at any season of the year.

During the prevalence of contagious diseases—when they shut on us everywhere the doors of the cabins, and talked of nothing but of massacring us—not only did he go unswervingly where he felt there was a soul to gain for Paradise, but, by an excess of zeal and an ingenuity born of Charity, he found means of opening all the ways that had been closed against him, and of breaking down, sometimes forcibly, all that opposed his progress. But that which imparted a more heavenly aspect to every such procedure, and did not result from human sagacity, was this, that, from the moment of his entry, he won over fierce spirits by a single word, and accomplished all that he had set himself to do. Nothing repelled him; and he always looked for good, even from souls the most hopeless.

He had a way of recourse to the angels all his own, and experienced their most powerful assistance. The savages, to whose aid he went at the hour of death, have seen him accompanied, as they said, by a young man of rare beauty and majestic glory, who remained at his side, and urged them to obey the instructions of the Father. These good people could tell no more, and inquired who was this companion who had so stolen away their hearts. They knew not that the angels do more than we in the conversion of sinners, although ordinarily, their operation is not so evident.

His strongest inclination was to aid the most depraved, however repulsive the disposition that any one might possess, however vile and insolent he might be. He felt for all alike, with the bowels of a Mother—not omitting any act of corporal Mercy which he could perform for the salvation of souls. He has been seen to dress ulcers so loathsome, and which emitted a stench so offensive, that the savages, and even the nearest relatives of the sick man, were unable to endure them. He alone would handle these, wiping off the pus and cleansing the wound, every day, for two and three months together, with an eye and a countenance that betokened only charity—though he often saw very clearly that the wounds were incurable. "But," said he, "the more deadly they are, the stronger inclination have I to undertake the care of them—that I may lead these poor people even to the gate of Paradise, and keep them from falling into sin at a time which is for them the most perilous in life."

Not one Mission was there in the whole territory of the Hurons in which he had not been; and several of them he had himself originated—that, in particular, in which he died. Toward the savages he conducted himself with a remarkable prudence, and with a sweetness of charity that could excuse all, and bear with all, though having in it nothing that was mean-spirited....

He was not so wedded to the conversion of the Hurons that his heart did not go out to Nations the most distant—were it only to baptize the infants, "who," he remarked, "are a certain gain for Heaven." He often said to us that it would have pleased him to fall into the hands of the Iroquois, and be their captive. For, had they burned him alive, he would at least have had a chance of instructing them for as long a time as they prolonged his torments; and, if they had spared his life, that would have been a precious means of obtaining their conversion—a thing impossible, as it is, the way being closed against us as long as they remain our enemies....

The full account, followed by a letter written by one of the Jesuit Fathers who buried St. Charles wrote, may be found here: Jesuit Relations, Volume XXXV.

Other posts on this blog drawn from the Jesuit Relations may be found here: