|

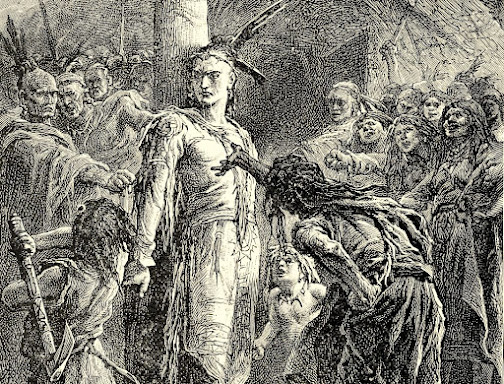

| Catherine Gandeanktena and her husband Francis Tonsahoten, as taken from the cover of Catherine of the Erie. |

Practically everyone has heard of Saint Kateri Tekakwitha, the Lily of the Mohawk nation and the first formally canonized indigenous American saint.

Almost no one has heard of Catherine Gandeaktena.

But a new historical novel, Catherine of the Erie by Claudio R. Salvucci aims to change that.

Though almost unknown among Catholics today, Catherine Gandeaktena's role was an important one. Indeed, if it were not for Catherine, the world may never have known about Saint Kateri. Catherine of the Erie successfully puts this devout, humble woman and her harrowing life story on the literary map.

|

| Newly published! Click here for more information |

Here is some historical background which will help the reader appreciate Catherine Gandeaktena's story as presented in this novel.

Catherine was a woman of the Erie nation. Like most of the other Iroquoian-speaking nations—among them the Hurons, Neutrals, Susquehannocks, and the Iroquois themselves—the Eries were a confederacy of tribes organized around clan alliances and living in semi-settled long-house villages. In the traditional scheme of things prior to European contact, the Eries were every bit as powerful as their neighbors, numbering perhaps in the tens of thousands. At the peak of their strength, they could field an army of 3-4,000 warriors.

In the 1640s when Catherine was born, the Erie nation was situated on the south shore of the Great Lake that bears their name even to this day. They were alternately known as the Nation of the Cat, as explained in the Jesuit Relation of 1655, "because of the prodigious number of Wildcats in their country, two or three times as large as our domestic Cats, but of a handsome and valuable fur." [from the Jesuit Relations as quoted in Iroquois Wars II, p. 108]

By 1650s, however, the political and military balance of power in the Eastern Woodlands began to shift rapidly. For one thing, the Iroquois, whose location in present-day central New York put them in close proximity to Dutch and English settlers, were able to acquire European weapons. With easier access to muskets and ammunition, the Iroquois soon became a terror to their neighbors. By 1649, the powerful Huron nation had been invaded, conquered, and scattered by the Iroquois. A few years later, the same fate befell the Neutrals. Over the next twenty years, the Iroquois would wear down and defeat even the powerful Susquehannocks in what is today central Pennsylvania.

The Eries knew that they war with the Iroquois was inevitable. But they were a warlike people themselves and many of their young warriors welcomed the conflict. Describing the Cats and their fighting prowess, Fr. Le Mercier writes:

"The Cat Nation is very populous, having been reinforced by some Hurons, who scattered in all directions when their country was laid waste, and who now have stirred up this war which is filling the Iroquois with alarm. Two thousand men are reckoned upon, well skilled in war, although they have no firearms. Notwithstanding this, they fight like Frenchmen, bravely sustaining the first discharge of the Iroquois, who are armed with our muskets, and then falling upon them with a hailstorm of poisoned arrows, which they discharge eight or ten times before a musket can be reloaded." [from the Jesuit Relations as quoted in Iroquois Wars II, p. 108]

In 1653, open warfare broke out between the Iroquois and the Eries. The Cats seemed to be the aggressors in the initial encounters as described by Fr. Mercier:

"They [the Iroquois] informed us that a fresh war had broken out against them, and thrown them all into a state of alarm: that the Ehriehronnons [Eries] were arming against them....They informed us that a village of Sonnontoehronnon Iroquois [the Seneca—one of the original five nations of the Iroquois confederacy] had been already taken and set on fire at their first approach; that that same nation had pursued one of their own armies which was returning victorious from the direction of the great lake of the Hurons, and that an entire company of eighty picked men, which formed the rear-guard, had been completely cut to pieces; that one of their greatest Captains, Annenraes by name, had been captured and led away captive by some skirmishers of that Nation." [from the Jesuit Relations as quoted in Iroquois Wars II, p. 108]

Click for more info.

It was the capture of this Annenraes which would ultimately bring doom upon the Eries. Reports of his torture and death lit a fire under the Iroquois confederacy who mobilized all their warriors and invaded the Erie homeland with guns blazing. The end result was the utter annihilation of the Cats. Once their fortifications were breached, the Iroquois attacked and slaughtered without mercy:

"Their boldness so astonished the besieged that, being already at the end of their munitions of war, with which, especially with powder, they had been but poorly provided, they resolved to flee. This was their ruin. For, after most of the first fugitives had been killed, the others were surrounded by the Onnontaguehronnons [the Onnondaga—one of the original five nations of the Iroquois confederacy], who entered the fort and there wrought such carnage among the women and children, that blood was knee-deep in certain places." [from the Jesuit Relations as quoted in Iroquois Wars II, p. 127]

During this period of horrendous cruelty and demonic vice (which I have previously chronicled here, here, and here among other places), it seems almost miraculous that such a gentle creature could emerge who, by her modesty, humility, and aversion to violence, appeared almost pre-disposed to Christian holiness.

Yet that was Catherine Gandeaktena.

Having been raised within a simmering cauldron of rage that featured regular displays of horrific torture and cannibalism, somehow Gandeaktena managed to remain aloof from all such excesses of wickedness. When her nation fell, Gandeaktena was made a slave and brought in cruel bondage to the villages of the Iroquois. Yet even as a helpless slave, Gandeaktena was able to win over others by her natural virtues. This description of her early life was recorded by the Jesuit fathers:

"God having permitted that Gentaienton, a village of the Chat nation, should be taken and sacked by the Iroquois, Gandeaktena, which is the name of the one of whom we are speaking, was taken into slavery together with her mother and brought to Onniout [a village of the Oneida nation of the Iroquois]. There the misfortune of her country proved the blessing of our captive. And her slavery was the cause of her preparing herself to receive through baptism the liberty of the children of God. The innocency in which she had lived, even before intending to become a Christian, seemed to have prepared her to receive this grace; and it is an astonishing fact that, in the midst of the extreme corruption of the Iroquois, she was able, before being illumined by the light of the Gospel, to keep herself from participating in their debaucheries, although she was their slave." [Jesuit Relation of 1679]

Later, Catherine Gandeaktena would become one of the founders of the Mission at La Prairie near present-day Montreal. This Mission would become a magnet attracting Christian converts among the nearby native tribes. So well-known would this haven become that the saying, "I am going to La Prairie," came to mean among the natives: "I am giving up polygamy and drunkenness."

Catherine died a holy death surrounded by the devout prayers of her husband, Francis Tonsahoten, and friends in AD 1673.

Four years later, in the autumn of 1677, a young Indian girl named Kateri Tekakwitha would arrive at the mission Catherine had helped to found which, by this time, had moved a short distance away and become a safe haven for converts to Christianity among the nations. It was here that Kateri's faith and devotion would grow, thrive, and achieve full flower. As told by Fr. Pierre Cholonec, her spiritual director and biographer:

"[W]hat edified her exceedingly was the piety of all the converts who composed this numerous mission. Above all, she was struck with seeing men become so different from what they were when they lived in their own country. She compared their exemplary life with the licentious course they had been accustomed to lead, and recognizing the hand of God in so extraordinary a change, she ceaselessly thanked Him for having conducted her into this land of blessings." [Kateri Tekakwitha: The Iroquois Saint, page 30]

Click for more info.

If you enjoyed reading this brief article about these heroic women of the wilderness, I encourage you to check out Catherine of the Erie. The novel brilliantly captures the life of Catherine and spirit of these harsh times, and has the advantage of being written by an author who really knows his stuff. Mr. Salvucci not only appreciates and illuminates the Catholic aspects of the story, but is also well versed in the history, folk-lore and languages of the Eastern Woodland tribes. In fact, several of the quotes above come from his work as co-editor of two volumes on the Iroquois Wars. And the frequent appearance of Iroquoian words and phrases throughout the novel is the product of his work as editor of a series of early Native American vocabularies and word lists.

Catherine of the Erie is a relatively short novel (about 160 pages) and is suitable for teens. If your young reader is particularly sensitive, be aware that there are some pretty intense scenes of warfare, as well as a dream sequence which is a little scary.