|

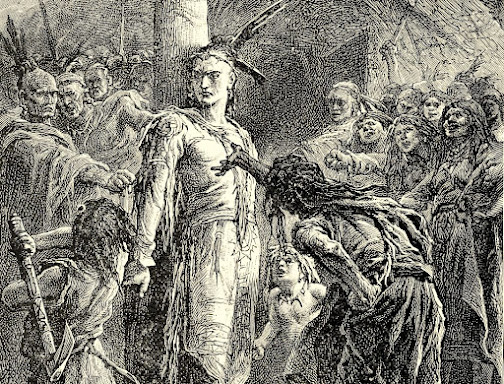

| Torture of a captive in the Eastern Woodands. Detail of a woodcut from Mason: True Stories of Our Pioneers, 1904. |

In my previous review of the novel Joseph the Huron by Antoinette Bosco, I mentioned briefly a scene in the book describing the capture and torture of an Iroquois prisoner by the Hurons. The details of this scene were drawn from the true story which appeared in the Jesuit Relations. Of course, Mrs. Bosco softened the story somewhat to make it more suitable for her audience of younger readers.

When writing the review, I revisited the original account of this prisoner in the Relations. Written in 1639 by an eye-witness—Jesuit Fr. Jerome Lalemant—I recalled the impression the account had made on me when I first read it some 20 years ago. Beyond the sheer cruelty and brutality of the scene, what strikes the reader most forcefully is the victim's supernatural courage in the face of certain death.

I post Fr. Lalemant's account here in part so I should not lose it again within the vast gulf of the internet. But I also post it so that those Catholics, who lack even a fraction of the fortitude of their forebears and who would apologize for their audacious missionary work among the indigenous tribes, may think twice. Indeed, may they shrink from such pusillanimous apologies once, twice, and every time they are tempted to offer them.

Without further ado, here is Fr. Lalemant's description of the death of the Iroquois convert Pierre Ononelwaia:

The common reaction of modern secular scholars to these types of accounts is as facile as it is dishonest. The claim is advanced that this and similar accounts were "fictionalized" or "exaggerated" by the Jesuit fathers. It is noteworthy that the one thing these critics often don't do in their long-winded attempts to excuse this type of grotesque brutality is quote liberally from the accounts themselves.

The first one baptized in this village was a poor unfortunate Hiroquois, a prisoner of war, who was taken to another village, near this, to be given as a recompense to the relatives of that brave Taratwane who was captured during these last years by the enemy, as has been mentioned in previous Relations. I do not know if I should not tarry for a moment to consider and admire the adorable Providence of God towards this poor wretch, and his fellow prisoners, to the number of 12 or 13, baptized by the Fathers of this Residence; but I prefer to leave these reflections to those who shall cast their eyes over this Narrative, and to stop only to observe some circumstances of these events which render them more important. For a long time, the Hurons had no more good fortune or advantage over their enemies until last year. Having gone to war, together with some Algonquains, their neighbors, they captured at one stroke about eighty of their enemies, whom they brought home alive. Besides this victory, the most notable of all, they had others of less importance, which in all gave them more than a hundred prisoners.

All those who were assigned to the villages where we have residences, or which are near these, were, thank God, instructed and baptized, and hardly one without circumstances so peculiar that there is reason to believe that there was, in their cases, some special guidance of divine Providence and of their predestination. In many instances, we had only the exact time necessary for their instruction and baptism; others, after having been baptized, were so comforted that they could not refrain from putting into song the cause of their consolation, — that thenceforward, at least, they were sure of going to Heaven. Others nobly refused to imitate foul and immodest actions to which their captors tried to incite them. Others afterward displayed so much fortitude in their torments that our barbarians resolved no longer to allow us to baptize these poor unfortunates, reckoning it a misfortune to their country when those whom they torment shriek not at all, or very little.

Indeed, this has given us so much trouble since then, that there has not been one of these for whose baptism we have not been obliged to give battle to those who are their Masters and Guardians; and sometimes it has been necessary to atone for this violence by some present.

Among those who showed most fortitude, and most appreciation of their good fortune, was one Ononelwaia, in baptism named Pierre, who was one of the prisoners at that principal defeat of which we have just spoken, a Captain of the Oneiouchronons [Oneidas], a nation of the Hiroquois. This man, being fastened to a stake upon a platform, not very far from his companion fastened to another — where our barbarians, every one according to his pleasure, tormented them, by the application of flames, firebrands, and glowing irons, in ways cruel beyond all power of description, and beyond all imagination of those who have not seen it — Pierre, I say, seeing this companion of his lose patience in the midst of these torments, comforted and encouraged him by representing the blessedness they had found in their misfortune, and that which was prepared for them after this life. Finally seeing him dead, “ Ah, my poor comrade,” said he, “ didst thou ask pardon of God before dying? “ — fearing that the evidence of suffering he had given was some grievous sin.

This brave spirit, who merited a better fate, was more tormented than ever by our barbarians after the death of his companion; for, the latter having died sooner than they expected, they all wreaked the rest of their fury upon him who remained. Accordingly, the first thing they did to him afterward was that one of them cut with a knife around his scalp, which he stripped off in order to carry away the hair, and, according to their custom, to preserve it as very precious.

After such treatment one would hardly believe that there could remain any sensation of life in a body so worn out with tortures. But lo! He suddenly rises, and, seeing upon the scaffold only the corpse of his dear companion, he takes in his hands, which were all in shreds, a firebrand, that he might not die as a captive, and that he might defend the brief liberty he had recovered a little while before death. The rage and the cries of his enemies redouble at this sight; they rush towards him with pieces of red-hot iron in their hands. His courage gives him strength; he puts himself on the defensive; he hurls his firebrands upon those who come nearest him; he throws down the ladders, to cut off their way, and avails himself of the fire and flame, the severity of which he has just experienced, to repel their attack vigorously. The blood that streamed down from his head over his entire body would have rent with pity a heart which had any remnant of humanity; but the fury of our barbarians found therein its satisfaction.

Some throw upon him coals and burning cinders; others underneath the scaffold find open places for their firebrands. He sees on all sides almost as many butchers as spectators; when he escapes one fire, he encounters another, and takes not one step without falling into the evil that he flees.

While defending himself thus for a long time, a false step causes him to fall backward to the ground. At the same time, his enemies pounce upon him, burn him anew, then throw him upon the fire. This invincible spirit, rising again from the midst of the flames — all covered with cinders that were imbued in his blood, two flaming firebrands in his hands — turns towards the mass of his enemies, to inspire them with fear once more before he dies. Not one is so hardy as to touch him; he makes a way for himself, and walks towards the village, as if to set it on fire.

He advances about a hundred paces, when some one throws a club which fells him to the ground; before he can rise again, they are upon him; they cut off his feet and hands, and, having seized the rest of this mangled body, they turn it round and round over nine different fires, which he almost entirely extinguished with his blood. Finally they thrust him under an overturned tree-trunk, all on fire, so that, at the same time, there may be no part of his body which is not cruelly burned. It was then that nature, before yielding to the cruelty of these torments, made one last effort, that could never have been expected. For, having neither feet nor hands, he rolled over in the flames, and, having fallen outside of them, he moved more than ten paces, upon his elbows and knees, in the direction of his enemies, who fled from him, dreading the approach of a man to whom nothing remained but courage, of which they could not deprive him except by wresting away his life.

This they finally did, one of them cutting off his head with a knife. Happy stroke which gave him freedom! For we have reason to believe that this brave spirit is now enjoying in Heaven the freedom of the children of God, since even his enemies loudly exclaimed that there was something more than human within him, and that without doubt baptism had given him his strength and courage, which surpassed all that they had ever seen.

Several Savages have reported with wonder, and a sort of conviction of the truths that we preach to them, that, shortly before he received the last blow which caused his death, he raised his eyes to Heaven and cried out joyfully, “ Let us go, then, let us go,” as if he were answering a voice that invited him. [Thwaites: Jesuit Relations, Volume 17]

Which is another reason I have done that here.